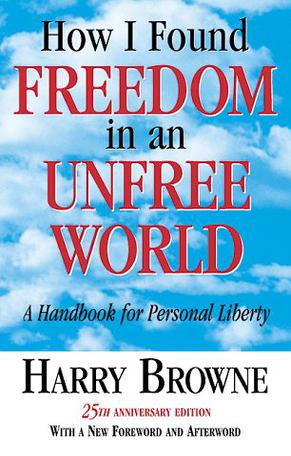

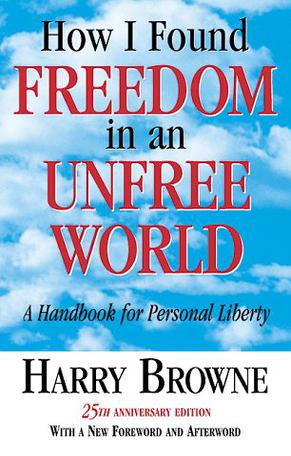

In this article I’ll discuss the book How I found freedom in an unfree world written by the American Harry Browne. This book is about personal freedom, a topic that often receives too little attention, in my opinion.

In this article I’ll discuss the book How I found freedom in an unfree world written by the American Harry Browne. This book is about personal freedom, a topic that often receives too little attention, in my opinion.

Loren Howe defined How I found freedom in an unfree world as “probably the most dangerous book ever written”, and I agree. In fact I’ve known about the existence of this book listening to that premise, I put my hands on it, I read it, and it was true: the power and the beauty of the ideas it contains not only hit me like a train, but they also brought meaningful changes to the way I think -first- and to my practical daily life -then-.

I want to remark that this is not the typical self-help book, in fact, as Browne himself explains in the introduction, he choosed the title “How I found freedom” rather than “How to find freedom” to clearly show that the ideas he talks about are not abstract, but they are achievable and possible because there is at least one person in history who put them in practice: him. He succeeded in increasing significantly his level of personal freedom. Now, with me I’d say we are at least two. But I’ll talk about me later.

Why should you care about freedom?

Why should you care about freedom?

The first thing to notice is that very few people care of increasing their level of personal freedom. Almost everybody accepts as inevitable a series of limitations that are imposed by the society, the government, the economy, the public moral, the parents, the friends, the common beliefs. All these causes can limit our freedom in several ways, creating what Harry Browne calls traps. Traps into which, in a certain point of our lives, we get caught.

A very valid point that Browne presents is in the affirmation that, it’s true, a life 100% free from the conditioning of these actors is unrealizable in the real world. On the other hand, it’s also true that today a lot of people accept to live with a degree of freedom of 20%, of 30%, while increasing it to 80%, to 90% is possible. It is possible. And such an increase in the degree of freedom brings huge positive consequences in life.

For this reason the author analyzes in his book the traps, one by one, those in which more frequently we find ourselves trapped and those that oppress us more significantly, explaining with an extraordinary simplicity that there is no reason to remain stuck inside of them: being free is as easy as opening the traps and fly away.

Create your own personal free world

Before commenting some of the most remarkable traps that Browne debunks in his book, I want to try to summarize the global message of How I found freedom in an unfree world, the way I understand it. The message is the following:

Do not wait that the whole world changes, before you can be free. Do not try you to change the whole world, before you can be free. Even in a planet full of problems, unfree people, dogmas and control structures that are huge and appearently very powerful, you can be free now: all you have to do is to create around you a subset of this planet in which you minimize the intervention (or in which you completely exclude the intervention, when possible) of those subjects that decrease your freedom.

You can be free even if the rest of the world is not, which is in fact the title of the book.

Consider that in the world there will still be wars, corrupted governments, unhappy families, abusive relationships, injustices for a long while. Maybe for ever. It makes no sense to live life repeating “if it wasn’t for the taxes/my wife/the job/the prejudice… then I would be free”. What makes sense instead, once identified a cause that limits your freedom, is to take positive decisions that allow you to reduce as much as possible the influence of that cause over your personal world, a world that you can populate mainly with people and structures that act according with your values.

This is a crucial point: we cannot decide how our familiars, our friends, our colleagues, our bank, our government deal with us. But we can surely decide how we deal with them. In particular, we can make choices that regulate the intensity with which these subjects are present and influent in our life.

And we can do this regulation because we have available a tool of enormous power: the power to take positive decisions.

What is a positive decision?

A positive decision is the one where you choose among alternatives in a way that maximizes you happiness. One example could be the one where you choose if you’d be happier going to the movies or to theatre.

Instead, a negative decision is the one where you choose among alternatives in a way that minimizes your unhappiness. One example could be the one where you choose betweeen repairing your roof, with a leak, and emptying your bank account.

As Browne writes, the typical characteristic of a free person is that he spends most of his time taking positive decisions.

Unfortunately instead, the large majority of people spend most of their time taking negative decisions, evaluating what alternatives are the less displeasant, trying not to make things get worse.

the reason why many insist in taking this second type of decisions is that they stuck in the traps. Common beliefs, that are taught to us and repeated to us since we are kids, but that really make no sense. These traps exist until exists the unawareness of having many different alternatives available, every time we make a choice.

Let’s see some of my favorites then, in the following I reformulate the ideas from the book and add my interpretations.

1. The previous investment trap

The previous investment trap is the belief that since in the past you invested a certain amount of resources (time, money, efforts) in an activity, in a relationship, in acquiring an object, that investment made in the past must condition the way you handle the activity/relationship/object also in the present.

The truth, the resources only have value until they’re not spent.Once that they are spent, they become completely ininfluent.

Here I immediately use a personal example: my career. I spent years at the university to get a difficult degreewhich is highly considered in the job market: engineering. I studied so many hours, spent money to buy books and to pay the university taxes. After graduating, following the common trend (“graduate and then go out and search for a job”), I found a job in a prestigious corporation, obtaining what at that time I considered a dream job.

Instead, despite the benefits, despite the career possibilities, despite everybody kept on repeating how lucky I was, after some years I realized it, that type of job made me unhappy. I had nothing to do with that environment, nothing to do with the people were working in it, nothing to do with the common values in the sector. In addition, I understood that even if I considered -and still consider- what I learned in my engineering studies very useful, I wanted to work in another sector.

If I stayd in the previous investment trap, I shouldn’t have abandoned that career because otherwise I would have “throwned away” all those years of study. This is infact what relatives, friends and acquantances repeated.

But the question is, exactly, in what way continuing to do a job I hated would have resurrected those years of studying? Would I have got back the hours spent on the books, or the money for the universitary taxes? No. Once I realized that the job was a source of unhappiness, the choice was simply between adding other years of unhappiness or peacefully accept that I took the wrong path, resign and start from that point a new path more in line with my values and where more likely I could find happiness.

Other examples are easy.

If you invested 20 years in a marriage and now you realize that the marriage makes you unhappy, should you stay in it to not “waste” the time you invested previously? No: it makes more sense to accept the new situation, save yourself other years of suffering and close. Maybe life has in store for you another relationship, and you can be happy at least from that moment on.

If you spent time, money and effort to buy and them rework a house, and after many years you notice that for whatever reason you’re not happy in that house, do you have to continue living in it to “legitimate” the resources you invested in the past? Those resources are lost anyway: you can sell the house and go to live somewhere else, where you can be happy from that moment on.

2. The utopia trap

The utopia trap is the belief that it’s necessary to change the world, aligning it with our standards of pleasant place, and changing others, convincing them to agree with our ideas, before we can be free.

It’s easy to fall into this trap because very often we see things that we consider wrong, for example: iniquitous laws that are approved, malicious behaviour by those who have the power, lies that are spread. Our reaction often is to fight to contrast these things, animatedly discussing with others, doing debates, jumping on the stages to rally people, doing protest marches. In fact, politics is the most classical destination for those who are trapped in the utopia trap.

What we typically try to do is to convince others to embrace our positions, because we want to create a better world, where we could finally feel free.

Well, the truth is that this behaviour not only leads us very often to frustrations, not only makes you waste a lot of your precious time, that you could use to enjoy your personal freedom instead, but more than anything else it’s not necessary.

Why trying to convince others is not the best strategy? Simply because we’re all different and each one of us see the world in a different way. It doesn’t matter how much an argument seems right, true and reasonable to you. It doesn’t even matter how solid and evident are the proofs that support your position. You will find a quantity of people who will ignore your argument or will even contrast it, no matter how good you are at explaining your thesis.

Thinking that what is true for you is true also for the others means to fall into another trap, the identity trap, which is the error of thinking that other people interpret the facts in the same way you do.

I spent a lot of time inside the utopia trap, and I had plenty of experience of the frustration it leads to. For example, I spent years trying to convince relatives and friends to adopt an healthy diet, to make them avoid self-injurious behaviours (like smoking), to agree on my political, phylosophical, spiritual views. And each time, after providing with emphasis proofs, motivations and explainations, I was definitely surprised, negatively, of how little my suggestions were received.

What I understood with time, and of which I had definitive confirmation reading Browne’s book, is that changing the opinions and the behaviours of people is yes possible, but there are two different approaches of doing it, and the first is less intelligent, the second is more intelligent.

The less intelligent method to produce change is all in this phrase: trying to convince others. Rarely it brings results. People don’t change simply because you push them to change. Some people will never change during their life, others change, but only when they will be ready and it will be their moment.

The second method is definitely a better strategy, and explains why some paragraphs ago I wrote that creating the ideal world, an utopia, to be free is not necessary.

This method consists of mainly taking care of our own freedom, ensuring that we are happy and fully satisfied. Living according to our principles and enjoy the consequent benefits. After that, instead of making pressure to convince others, give them some indications. Maybe just even with our own example.

Those who will be interested to the indications we give, will probably follow them. If we’ll be lucky we will have the chance to enter in relationship with those people and enjoy the similarity of views. Instead, it doesn’t make sense to waste our time and energies trying to deliver those messages to who’s not ready to receive them.

If one day the world will reach the stage when a critical mass of people, individually, will be ready to understand a certain message that is valid for us, then probably there will be a global change in the direction that seems “good” to us. But in the meanwhile, it’s important to give priority to our personal freedom, without continuously postponing it waiting for an utopia to happen.

Politics produces change?

Note, as consequence of the utopia trap, that politics is a method to achieve change that is often very inefficient, since it’s founded on the ability to convince others. The job of the politician itself, especially in democracies, starts only after a certain amount of people have been convinced to give their vote to this or that other party.

I think that the role of politics is misunderstood by many, and especially that often it is credited to it an exxaggerated importance compared to other factors that are more determinant to produce changes in the society.

3. The government trap

Harry Browne defines the government a “fascinating topic”. I guess he kept his focus mainly on the operations of his own government, the American one. I think that if he saw the operations of the Italian one he would have probably written the same things more or less, but I wonder if he could have resisted to add a comic vein, considered the big number of dwarfes, jugglers, burlesque and sluts that populate the political scene in Italy.

What Browne writes in How I found freedom in an unfree world can even be shocking at the first reading, especially considering that for ever we have been used to the fact that there is a government, to turn to the government when we have problems, to believe that the government performs socially useful actions.

But is it true? The government adds or subtracts value from our lives?

Browne writes it rather clearly: usually the government creates problems, rather than solving them. If a government that today is composed of n representatives tomorrow doubles its dimension and become of 2n representatives, not only the problems would not diminish, probably a lot of new problems would born.

Why should this happen? Simply because the government intervenes on the free market, the place where the citizens trade goods and services according with their desires, walking over their will and “doping” the supplies. This is in synthesis what a government does: it performs an action which is coercive for the individuals.

Just to make a practical example, related to the period in which I’m writing this article, in Italy there is an airline that doesn’t work at all in the market. The customers prefer to fly with other companies, that are cheaper and that satisfy their needs better. Despite this, the Italian government continues to subsidize this malfunctioning airline, at loss since many years, using the money from the taxes. This way it protects the interests of few groups of powers connected to it.

As a fact, the free market is indicating that this airline must go out of business. If there would not be the doping intervention of the government, the inefficient airline would close and new opportunities would arise for new realities in the sector of air transportation, that could bring innovation and provide a better service for the customers.

A lot of examples of this type can be made, they all lead to the same conclusion: the government is a group of people that doesn’t know exactly what the single citizen wants, or it’s just not interested in solving his problems, or it’s not able to.

As Voltaire wrote: the art of government consists in taking as much money as possible from one class of citizens to give to the other.

The brilliant point that Browne develops is about how to defend ourselves from the coercive actions of the government.Often it looks to us as an entity so big and powerful that we have no chance to be free from its restrictions, its obligations, its taxes.

So here there is an important concept, which is valid not only for the government, but also for all the other oppressive structures of big dimensions: these structures of control that try to limit our personal freedom are big and slow, while we as individuals are small and fast. Using this characteristic of being small and fast, we can still succeed well in our mission of living in a predominantly free world.

We must always remember in fact that we have the possibility of taking positive decisions. For example, to avoid the high taxes that a government imposes, we don’t necessarily have to evade them or to commit in political action to reduce them: we can simply choose a job in which the taxation level is lower, or choose a country where the taxes are lower.

For example I that the tendency that the media have -to give merits and write in positive terms of the entrepreneurs who “resist” with their activity in Italy, despite the Italian government applies very high taxes to entrepreneurs- doesn’t make sense. These entrepreneurs have to carry on their activity with many more efforts and working harder.

What the media do, in reality, is to praise the attitude to slavery of there entrepreneurs who resist. Frankly, I don’t see much sense in keeping on hitting the wall with the head, staying connected to a government that becomes progressively more abusive, in the name of “continuing to produce in Italy”.

Instead I see much more sense in the choice that other entrepreneurs do (on these the media point a negative light, of course) to go outside of Italy, bringing the production estabilishments in countries where the taxation is more favorable.

The latter looks much more like a positive decision.

4. The unselfishness trap

No one knows you as well as you do. Not your mother. Not your children. Not your wife. Not your friends. Not the bank. Not the government. You are the one who knows yourself better.

What descends from this statement? That no one in the world knows better than you what you need to be happy. You are the best person to turn to. Focusing instead on others, your wife or the government, expecting that they act in altruistic way and make you happy is a strategy that doesn’t make much sense. Even if they’re moved from the real desire to make you happy, they have less chances than yourself to succeed, simply because they are not you.

This is valid also in the other direction: we’ve been instructed to be altruistic and not be selfish, when the opposite makes sense. Living your life putting before indiscriminately the happines of others to your own personal happiness, not only will make you unhappy, but very often will not even make the others happy. Because the others need different things, from the things you think, to be happy.

I observed that often is much more pleasant to stay around people who are focused on their own happiness, like kids. Kids have not been trained yet to make choices that go against their own interests to avoid being considered selfish.

This doesn’t mean that sometimes it’s not pleasant to act in a way to make happy the people we have around, especially because later we can also benefit from their happiness, but what surely doesn’t make sense is to do it indiscriminately and with the fear of appearing selfish, otherwise.

5. The box trap

With box Harry Browne means every situation of discomfort you are in and that limits your personal freedom.

It could be a job you don’t like anymore, a ritual lunch with tedious relatives, a social obligation you feel you have to partecipate to.

The point made about this trap is very simple, and it’s not even a schocking revelation, but it’s the prominence that is given to the following concept, that I find very appropriate.

The concept is this: everything has a price. There’s a price for changing things and coming out of the box, but there’s also a price for not changing things and staying inside the box. You pay this second price in instalments, day after day, for all the time you stay inside.

What happens is that a lot of people accepts a limitation to their personal freedom because they think that the price to pay for coming out of the box is too high, but I think that the real reason why they stay closed inside is that they fail to see the real identity of the price.

I use again my personal example of leaving my previous career. When I was evaluating if leaving or not, I took some time to reflect on the scenario I would have faced if really I had taken the decision of leaving. I understood that the heavier price -for me- necessary to get free of the job I hated was not the uncertainty of what to do after, or the possible economic difficulties I would have faced, but the strong opposition I would have had from relatives and friends, and the suffering I would have caused to my parents.

After some thinking, I decided that I was definitely available to pay this price to get free of my box. In fact, I clarified with myself that I gave so much value to the possibility of managing my own time and to do a job I was passionate for, that I would have paid much more than this.

This is again a professional example, but it’s easy to extend to other fields: romantic relationships, social obligations, moral obligations and so on.

In general, as Browne suggests, when you’re evaluating if coming out of a box, it’s conveniente to anticipate mentally the possible scenarios that could realize in this operation, all of them, and evaluate how to reach in front of each of them.

There are always many, many different prices that can be paid to get out of the boxes in ways that increase significantly our personal freedom: cultivate the art of searching for the prices each time you are in a situation of discomfort.

6. The rights trap

The rights trap is a concept where Harry Browne really shines, because he expresses a very simple and a very original idea, that I found definitely intelligent.

The rights trap consists in believing that your rights will make you obtain what you desire. Classic example: how often we hear discussions about civil rights? And how many of us are grown with the idea of having the right to property, the right to be treated with respect, or to have a job?

The most interesting point about rights is this: they imply the existence of someone who doesn’t want to give those rights to us. Otherwise, we would not even talk about it.

An homosexual couple would not invoke civil rights, if there weren’t other people who don’t want that the same-sex marriage is approved. A precarious worker would not invoke the right of having a job, if there wasn’t the entrepreneur who would want to fire him. A tenant would not invoke the right to have a house, if there wasn’t the owner who wants him to leave his house.

Browne considers three different ways to obtain what we want:

- Invoke our rights

- Act in a way that what we want is also in the interest of the other person

- Obtain what we want without involving at all the other person in the situation

In agreement with the author, I also found myself in situations where I experienced that the second and third method work better. Invoking our rights often means searching for support from the government, the associations, consumers groups, that produce unsatisfactory results (sometimes even null results), especially considering, in fact, the efforts spent in the “battle for the recognition of rights”.

A very fitting exaple is the marriage for homosexual couples. In Italy and at the moment of writing for example, it’s still not recognized legally. Periodically and fruitlessly, the debate starts between those who want a law to have it approved (“it would be a sign of civilty”), and those who oppose because not acceptable according to their values. Every tot of time there is a protest march, a manifestation, a talk show in television where the flame burns again.

Actually, for homosexual couples who want to get married there is a simpler solution (which makes perfectly sense also for heterosexual couples) that belongs to modality 3: obtaining the marriage without letting the opposer get in the situation at all. Possible? Totally.

Thinking about it, it would make sense if marriage would a contract of two, because two are the people in love and who want to get married.

Instead, with marriage a lot of people try to give birth to a contract of three, sometimes even of four. The contract of three involves the spouses plus a religious entity, or the spouses plus an governative entity. The contract of four involves the spouses plus the religious entity plus the governative entity (pure masochism?).

There is no need to involve in the marriage the religion or the government: if you want to get married do it, with a party in front of your friends, of your relatives, of those who love you, without any need from an external entity who give you “permission” or his approval to be united. You could let a kid, or a friend who knows you and loves you, celebrate the marriage. Wouldn’t he have more authority for you than a stranger in uniform?

Behind the request of a law that approves homosexual marriage is often hidden, by homosexuaol people, the hope that after the approval of such law their identity would get recognized and the intolerance and homophobic behaviours would decrease, but it’s not like this. If you’re homosexual, who hates you for being homosexual will keep on doing it even if homosexual marriage becomes legal. It’s very likely that you will not make him stop by claiming your rights, on the other hand you have great chances of excluding him from your life.

Isn’t it wonderful?

The other traps

There are several other traps, typical limitations to our personal freedom, that Harry Browne discusses intelligently in How I found freedom in an unfree world.

Many of these descend from two main traps:

– the identity trap, that the author actually presents first in the book, it consists in the belief that you have to be someone different from yourself, and in the assumption that others will do things in the same way you would do them.

– the group trap, the belief that you can reach your goals better if you share responsibility, efforts and rewards with others, compared to what you can do acting alone.

I avoid to enter in the details of all the traps because, on the wave of the enthusiasm that I have for this book -that I consider very precious-, I would probably end up writing a second version. I close instead, beside with the suggestion of putting your hands on it as soon as possible, with a last message that I consider important.

Your freedom is your own task

In this article I associated often the adjective “personal” to the word freedom for a precise reason: the responsible for your freedom is you and no one else. Don’t consign it to the government, to your children, to your partner, to none of the people closer to you.

You arrive on this world and you find in it some programs, some structures, some thought patterns already pre-packed by those who passed on the world before you. You find a government done in a certain way, a public morality intended in a certain way, social relationships conceived in a certain way.

You have no duty to accept these ways.

Freedom means living your life the way you want to live it. It doesn’t mean living it the way I, Paolo, tell you, how Harry Browne tells you, or anyone else. You can know yourself better than anyone else (know yourself, enormous wisdom from ancient Greece): use this knowledge to select the part of the world that you need to be free.

Good luck!

… and I?

I read How I found freedom in an unfree world several years ago now. As i wrote at the beginning, its ideas brought evident changes to my way of seeing and doing things. Some of these changes are:

– I quit my corporate job to become an entrepreneur, today I focus mostly on jobs I am passionated about, always being careful to have a good amount of free time. I can peacefully say that I prefer to work few hours a day, without feeling guilty because I’m not “productive”, a sort of obligation I felt until some time ago instead.

– I diminished the time spent trying to convince others, stressing myself, and I made peace with the idea that a lot of people simply don’t want to be helped. I still enjoy political and social activism, but I do it with a different spirit, and more targeted.

– I consciously loosened some relationships with long time friends and acquaintances, not very interested to be free, and I had the luck to start new ones with people who are closer to my values. I also learned that no matter how much, a lot, I love my parents, my sister, my closest friends, sometimes they are the most insidious obstacles between me and my freedom. I learned to fight them with determination, when I recognize that their advice is based on fear.

– I oserve what the government does with interest, and I talk with my friends and joke about it… but in the meanwhile I go on with my projects.

– I increased considerably my level of honesty, even if for now I’m still far from the 100% level of honesty I aspire to. Harry Browne’s book made me understand, even more, how being ourselves is one of the most powerful tools to get to freedom, but also one of the most rarely used in the planet. This is a very big work in progress for me, in which I’m working (hitting my head on the wall a lot).

In general, I recognize that reading the book had on me the ffect that now I do more introspection, I listen more to my intuition, and certainly I developed a healthy critical sense regarding the big institutions, especially politicals, banks, pharmaceuticals, religious.

Let’s say it clear, I still have a lot of work to do. A lot. Increasing personal freedom in fact means hard work. But I use this book as a guide, and it helps me a lot.

Notes: Translated from the original article in Italian, published on date August 31, 2014.